Lincolnshire’s Medieval Standing Crosses

What (and why) are Medieval Standing Crosses?

Standing crosses were a commonplace part of the English medieval landscape – every village and town would have had at least one . . . probably several. We tend to think of them as stone structures, but that’s just an aspect of their survival. Presumably a significant proportion of standing crosses were fashioned in timber although arguably those of stone may always have had a higher status.

Most of the standing crosses in England were destroyed or partly demolished in the Reformation or the Civil War. Some remnants survive and this website presents a gazetteer, and a clickable map, of all the known standing cross remains in the historic county of Lincolnshire.

Lincolnshire has the remains of about 200 later medieval stones crosses – now in varying stages of decline. As noted elsewhere on this website, the iconoclasts of the Reformation (16th C) and the English Civil War (17th C) systematically destroyed the symbols of the Roman Catholic church and any decorations or artefacts that could be deemed idolatrous. Standing crosses, being part of the paraphernalia of religious processions, were usually decapitated or demolished but those crosses which had a more secular function, such as market crosses, were often spared, even though they may once have been part of the Catholic processional routes.

This website presents information and photographs of all the known crosses in Lincolnshire within its gazetteer pages. You can move straight to the gazetteer index – HERE.

There is also a clickable map to show where they are – HERE.

Standing crosses are fundamentally religious symbols and they all served to remind passers by of God’s presence and power. However, in real life they also had very practical functions. Many were erected to mark and consecrate graveyards and also to serve as stations for outdoor religious processions – notably on Palm Sunday, Rogationtide and the festival of Corpus Christi. Others gave validity to meeting places and market places.

Medieval Standing Crosses generally rate amongst the most undervalued of ancient monuments and, admittedly, most standing cross remnants are unremarkable. But we do have some good ones, and if we were to pick the TOP TEN medieval crosses in Lincolnshire we might choose:

Many medieval standing crosses are found in churchyards but are often later in date than the church itself, negating any suggestion that the cross is an early meeting point for worship and preaching. Churchyard crosses are probably part of the processional cycle although there is also a clear case for some being rehomed into churchyards from other parts of the village as lifestyle and streetscape changed with time and the crosses became surplus to requirements.

Crosses were often erected in the communal areas of a town or village – the village green or town square – which usually served also as market place and a gathering place for proclamations and public meetings. A market cross (sometimes termed a Butter cross) was a symbol of fair and honest trade (carried out under the eyes of God) and the structures themselves evolved from simple standing crosses set on steps to quite elaborate buildings surmounted by the cross, validating the transactions being carried on beneath. The authority of the market cross extended to it being the right and proper place for the proclamation of important news and statements and thus the site of the cross becomes the focus of not only religious significance, but of civil solemnity and status.

Almost all the standing crosses in the UK were defaced, decapitated or destroyed at the reformation or in the Civil War. The cross heads (in all their varieties) have mostly been smashed, leaving at best a section of shaft still set in its base mounting or at worst a lonely, displaced socket stone. They are thus, one of the least valued and understood monuments of the later medieval period.

The cross remains described in this website are mostly thought to be twelfth to sixteenth century in origin – The remains of some forty ‘Saxon’ crosses are known within the county and it is not proposed to describe these in detail, for that has already been admirably done in The Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture – Lincolnshire (Vol 5) by Paul Everson and David Stocker. See: https://chacklepie.com/ascorpus/catvol5.php

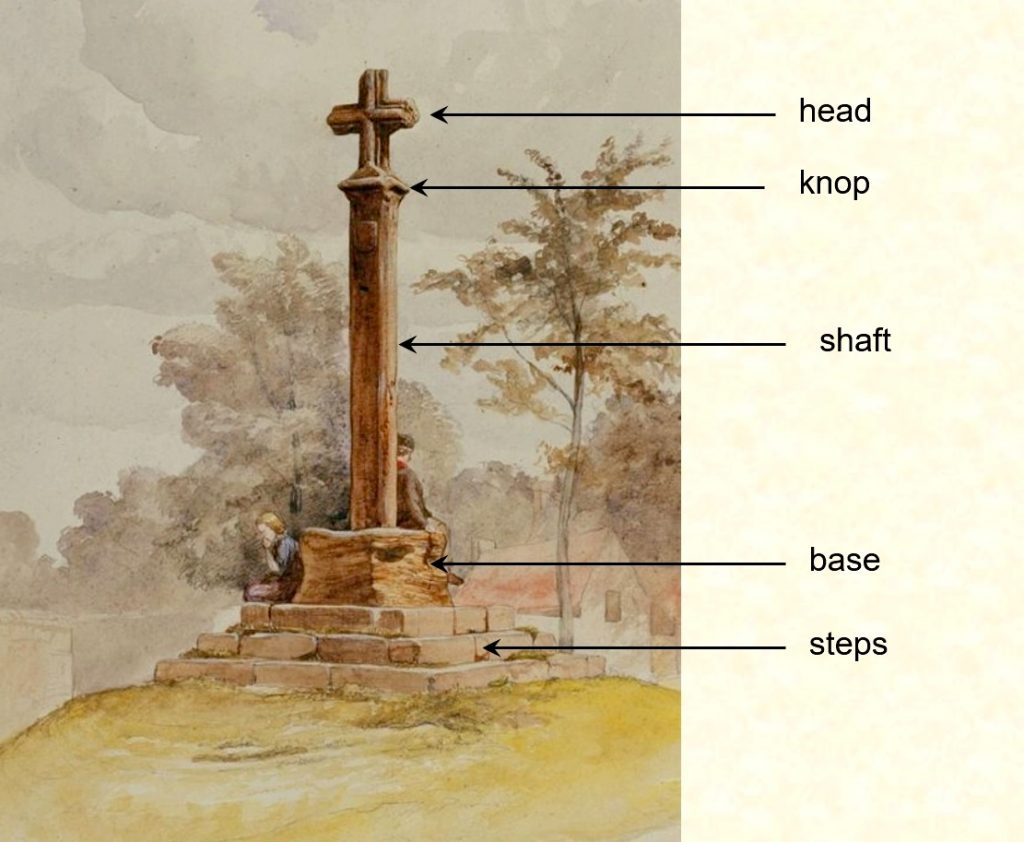

The Anatomy of a Medieval Cross

CROSS HEADS : because these were the main target of 16th and 17th century iconoclasts, few have survived. A very wide range of designs were employed. Replacement heads are often found.

KNOP : The terminal of the shaft and usually integral with it. Often simple, occasionally elaborate. As with cross heads, they rarely survive.

SHAFT : Usually square or octagonal. Generally a single piece of stone – but many survivors are repaired.

BASE or SOCKET STONE: (occasionally called a ‘socle’)- Usually square with a central square socket for the cross shaft. The corners are often decorated – on notable examples, the side faces are carved.

STEPS : Some crosses are mounted on two or three steps – others have none (just a socket stone). Market crosses may have many steps, and thus have a very broad base.

Roadside shrines are common in many parts of Catholic Europe and are similar in many ways to English medieval standing crosses